Ikat is a resist-dye weaving process where unwoven threads are tied off and dyed. Before threading the loom, the yarn is separated into long strands and subjected to a process similar to batik: individual or small bundles of unwoven threads are bound tightly in certain places, to prevent dye from adhering to those areas, and then dyed. The word ikat is of Indonesian origin and means to tie or bind. Ikat textiles are produced all over the world, especially in Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan and Central Asia, and predominantly created with the double ikat method, i.e. by resist-dying both warp and weft. However, in Uzbekistan only the warp yarns are bound tightly and dyed.

In Uzbekistan ikat fabrics are called abr, an originally Persian term meaning cloud. Thus abr-bandi, cloud-tying, refers to the binding technique that gives ikat its characteristic cloud-like pattern. The process of intricately tying off and resist-dyeing the threads is mostly carried out by special ikat masters. In the past, the dyeing process required more than one dyer, as each one was skilled in a specific colour.

Once the dyed threads have been threaded onto the loom, the pattern is clear to see, and the actual weaving process is relatively straightforward.

During the Soviet era, at first ikat fabrics were made by hand in craftsmen’s cooperative unions known as artels. These exceptional ikats were eventually supplanted by those produced by the large textile combines established by the Soviets in Uzbekistan during the 1960s and ‘70s. While the patterns were still created manually, machines were already being used to some extent to bind the threads, and eventually the weaving process was completely automated. The combines were also not very diligent in their use of synthetic dyes, and, as a result, many textiles produced between 1970 and 1990 are not colour fast.

Today most ikats made of atlas are machine woven. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union there has been a large, government-funded initiative to encourage manual crafts. Particularly in the Fergana Valley, the numbers of manufacturers producing ikat completely by hand has grown exponentially – it is here that ikat textiles are produced for fashion companies like Gucci or Dries van Noten. Just how keen the government is to re-establish this craft is demonstrated by the fact that craftsmen are exempted from paying taxes, among other incentives.

It’s practically impossible to find the genuine faux-ikat prints known as doppis, which inundated the Central Asian market from 1960 to 1990. On the other hand, many traditional textile skills and techniques that had been neglected for years revived, such as the production of baghmal, a thick, fluffy silk velvet ikat. As well as pure silk ikats, adras is another important Uzbek textile. It’s a durable, wonderfully shiny fabric with a silk warp and cotton weft. The striped variety is called bakasab, which is also used for ikat. Which is just as well!

Read more about the textiles in Uzbekistan.

Bilder von oben nach unten:

1. Teacher with students in Samarkand. Sergei Mikailovich Prokudin-Gorskii, between 1905-1915. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

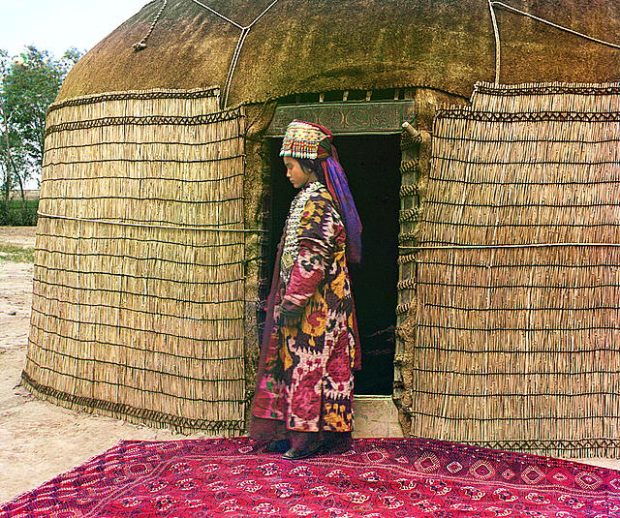

2. Turkmen girl in front of a jurt. She is wearing minimum two coats above the other, the coat on top is a silk ikat. Sergei Mikailovich Prokudin-Gorskii, between 1905-1915. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

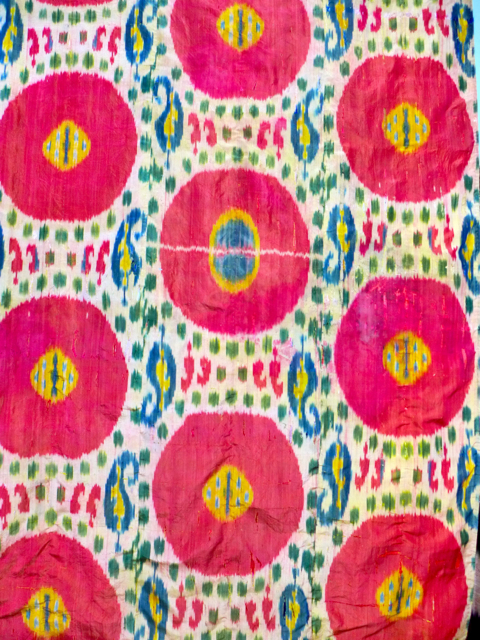

3. Wonderful old ikat, seen at the Akba-Gallery in Bukhara.

4-6. Here you can see the dyed warp during preparation for the weaving.

7. Uzbek woman at the bazaar in Bukhara in a typical modern traditional styled ikat print.

8. Even such patterns are made with the ikat technique. If you can. Seen at the Akhba Haus in Bukhara.